Thursday 13 July 2023

Milton Court Concert Hall

Guildhall Jazz Open Day

2pm Guildhall Big Band plays Oliver Nelson

Matt Skelton director

Tony Kofi alto saxophone

Miguel Gorodi trumpet

7.30pm Guildhall Jazz Orchestra: Aura

Scott Stroman director

Palle Mikkelborg composer

Robbie Robson trumpet

Milton Court

Please make sure that digital devices & mobile phones are switched off during the performance.

Please do not stand or sit in any gangway.

Eating is not permitted in the auditorium.

Drinks are allowed inside the auditorium in polycarbonates.

Filming or recording of the performance is not permitted.

Latecomers will be able to enter the auditorium at a suitable break in the performance.

Print at home

This digital programme is intended for mobile devices, and may be viewed throughout the performance. If you would prefer to bring a hard copy with you, please follow the link below to download a print-friendly version:

Digital Concert Programmes at Guildhall School

Thank you for accessing the digital programme for Guildhall School's Jazz Open Day. Over the course of our 2022–23 season we have been trialling digital programmes to reduce the environmental impact of our performances, improve accessibility and offer additional online material to enhance the audience experience. After the performance, please let us know what you think by filling in the survey below:

Guildhall Big Band plays Oliver Nelson

Matt Skelton director

Tony Kofi alto saxophone

Miguel Gorodi trumpet

Guildhall Big Band are joined by special guests Tony Kofi and Miguel Gorodi for this tribute to the majestic and powerful music of composer, arranger and saxophonist Oliver Nelson, and a celebration of its ability to enlighten and educate.

Matt Skelton directs this special matinee performance, featuring selections from Nelson’s landmark suite for jazz orchestra Afro-American Sketches. This represented Nelson’s first full recording of original big band material and explores racial and political themes that galvanised much of his work. Sketches, composed and recorded in 1961, came out of Nelson’s time studying the musical traditions of nearly 200 African tribes. Its seven movements follow a story that begins on the African continent, suffers the evils of slavery, experiences the temporary joy of rediscovered freedom, expresses the pain of societal oppression, and looks with optimism toward a future that embraces equal rights for all people.

Programme

Miss Fine

Step Right Up

I Remember Bird (Leonard Feather, arr. Oliver Nelson)

Blues & The Abstract Truth

feat. Tony Kofi

Midnite Blue (Neil Hefti, arr. Oliver Nelson)

feat. Tony Kofi

The Sidewalks of New York (aka "East Side, West Side") (Lawlor & Blake, arr. Oliver Nelson)

Stolen Moments (vocal arr. Clare Wheeler)

Emancipation Blues

Message

Night Train (Jimmy Forest, arr. Oliver Nelson)

Personnel

Voice

Amy Hollingsworth

Nel Begley

Anni Delger

Cello

Cubby Howard

Woodwind

Tony Kofi (solo alto)

Benjy Sandler (alto)

Jack Devonshire (alto)

Florence Redmonds (tenor)

Chris Clayden (tenor)

Reuben Dakin (baritone)

Trumpet

Jack Ross

Edward Hogben

Sam Tarlton

Miguel Gorodi

Trombone

Leon Middleton

Sam Cox

Max Lawrence

James Greer (bass)

French Horn

Alice Warburton

Henry Ward

Josh Pizzoferro

Guitar

Bryn Powell

Piano

Will Inscoe

Bass

Ygor Alvarez Azevedo

Mark McQuillan

Drums

Lester Ridout

Josh Davis

Guildhall Jazz Orchestra: Aura

Scott Stroman director

Palle Mikkelborg composer

Robbie Robson trumpet

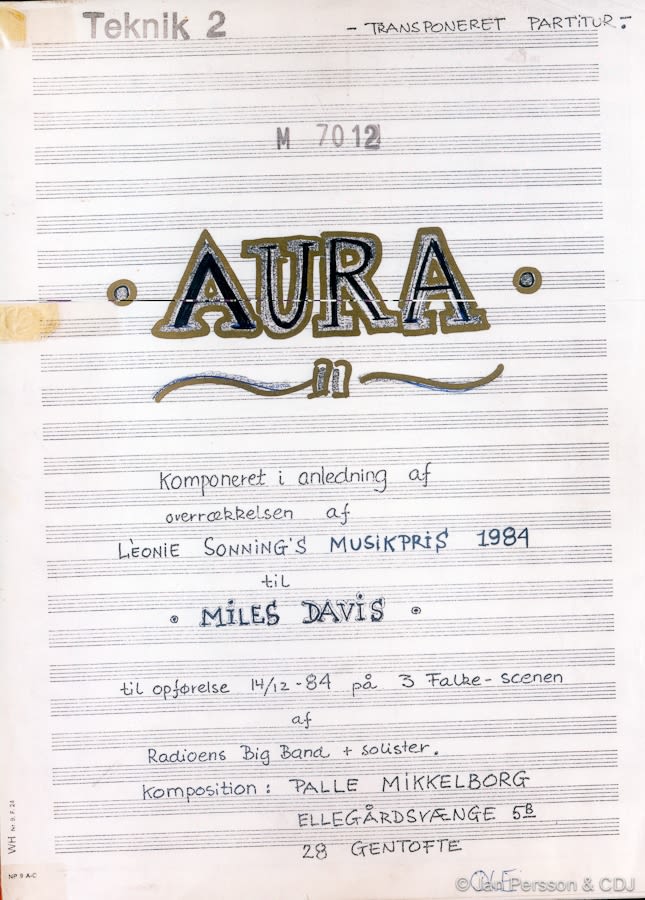

Composed in tribute to Miles Davis in 1984, and the final album to be released during his lifetime, Aura saw Miles collaborate with Danish trumpeter Palle Mikkelborg to create a unique conceptual work. The ten movements encompass everything from blues to funk to reggae, and represent, in the broadest possible terms, what writer Herb Wong described as Miles’ “charismatic and nutritious aura”.

The work’s main theme consists of ten notes generated from the letters ‘M-I-L-E-S-D-A-V-I-S’, with each movement representing a different colour of Davis’ aura as seen by Mikkelborg. It was described by Fred Kaplan of New York magazine as a “jolting synthesis of jazz, rock, and Messiaen-influenced classical music that lit up a future path lamentably unfollowed”.

In this concert performance, Guildhall Jazz Orchestra – under the direction of Scott Stroman and with special guest trumpet player Robbie Robson – return to the original orchestral score to present a fresh look at the material that was to become one of Miles’ finest works for the final decade of his life.

The performance will begin with a pre-recorded audio track and excerpts from the documentary Days With Miles: The Making of Aura and a recent recorded conversation between Palle Mikkelborg and director Scott Stroman.

This performance of Aura will be as close to the composer’s original vision as possible. Mikkelborg conceived the suite as an all-embracing live experience, a through-composed colour journey through the auras of Miles to be travelled together.

Aura

by Palle Mikkelborg

Intro

White

Yellow

Orange

Red

Green

Blue

Indigo

Violet

White

Personnel

Guildhall Jazz Singers

Nel Begley

Anni Delger

Sam Gale

Roza Herwig

Amy Hollingsworth

Will Inscoe

Alex Moss

Trumpet Soloist

Robbie Robson

Woodwinds

Harrison Perkins (alto/flute/soprano/clarinet)

David Whyatt (alto/flute/alto flute)

Maddy Coombs (tenor/flute)

Will Rees-Jones (tenor/flute/soprano)

Emily Irvine (baritone/flute)

Chris Clayden (bass clarinet/clarinet)

Oboe/Cor Anglais

Charis Lai

Trumpet/Flugel

Josh Elcock

Oli Arnold

Jack Ross

Freya Mallinson

Luke Lane

Trombone

Felix Fardell

Connor Martin

Josh Brierley

Sam Cox

Josh Cargill (bass)

Guitar

Jakub Klimiuk

André Marques Moreira

Harp

Alicja Cetnar

Piano/Keys

Cody Moss

Miles Lavelle Golding

Bass

Matthew May

Olly Meredith (double bass)

Nigel Feldman

Drums/Percussion

Anmol Mohara Darji

Tom Blunt (electronic drums)

Percussion

Jake Rees

Tape

Scarlet Halton

Welcome to Aura

I know of no other piece quite like Aura. Of course, on first hearing, it is the unmistakable voice of Miles which catches the ear, but there is something about the setting, the larger piece, which stands it apart from any other Davis recording since the 1960s. It is the voice of another musician, one who seems to know how to draw out the best in Miles in a large palate; one who somehow, from a distance, shares his world. I know of only one other, Gil Evans, who could do that. Palle Mikkelborg walks in his footsteps.

Palle was someone I knew more from reputation than from listening, in retrospect a huge oversight on my part, but when I heard Aura I knew both that I wanted to bring it to life, live, and that I wanted to get to know its creator. Both did not disappoint. After a 25-year attempt to make it happen, it finally has, thanks to Adam Williams' unearthing of its score in the Danish Radio library, Stuart Hall's remarkable achievement in extracting performing materials, and the dedication of all the young musicians on stage. And Palle revealed himself to be a generous, modest, and kindred spirit while hosting me in Copenhagen over two life-enhancing days to discuss music, life, and Aura. His current health doesn't allow him to travel to be here, so I went to him.

Aura is an ambitious undertaking, requiring a large group of musicians and integrating sounds from the period including tape, bespoke synthesizers, and electronic percussion, in addition to Palle's beloved oboe and harp. To our surprise we discovered that the Grammy Award-winning record was quite different than the original score, created for one special broadcast concert. Through-composed but with clear sections ("colours"), it was not only subtly biographical but referenced previous winners of the prize Miles was to receive, and had long stretches of calm introspection. The recording had been adapted, beautifully, by Miles and Palle for a home listening experience, in tracks. But, as Palle says, it is a different piece.

To his delight and mine, we present it in its original concert form, designed for one special moment and not performed since - until now, which happens, coincidentally, to be the 40th anniversary of its composition. I asked him why, in spite of many requests, it had not happened since. He looked me in the eye, and said, surely meaning all of us, "because I did not have you". Bless you, Palle, for the love you bring through your music.

-Scott Stroman

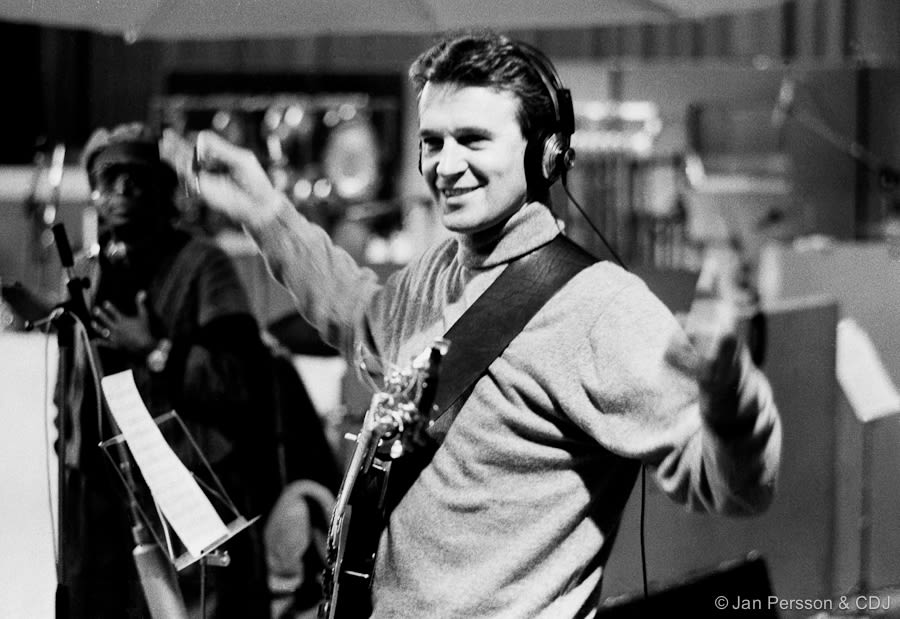

Scott Stroman and Palle Mikkelborg

Scott Stroman and Palle Mikkelborg

Interview with Palle Mikkelborg

by Scott Stroman

Extract from interview transcription, taken 26 June 2023

Scott Stroman: Would you say that Aura is about your feelings about Miles Davis?

Palle Mikkelborg: Exactly. Because that was what they [Leonie Sonning’s Musicpris] asked me to do: ‘He should only play 5 minutes’. I didn’t know that one night the telephone [would ring] in ’84 and I would hear [Miles’] voice: ‘Hey! Palle!’ I thought it was a friend of mine, joking! But it was actually Miles saying ‘I want to record this’.

Funnily enough, he had a little tape recorder with him, an old tape recorder, you know? Where he’s recording on cassette. So he heard that and said ‘I want to record that’. He said ‘Can you make it in ten days or something like that? We will come.’

SS: So he had the concert and he had this little recorder and he had recorded some of it himself?

PM: He recorded some of it and listened to it and then he said ‘I’ll be there’.

SS: Did you actually do it on short notice like this?

PM: We did! In Easy Sound [studio in Copenhagen] and [Miles’] staff arranged it so that the band was there. We picked up soloists [even though] some of them were supposed to go on holiday or whatever. They said ‘No, No, Miles is coming. We will skip everything to be there when he’s there.’

SS: So they made the [Danish] Radio [Big] Band available and changed everything they were going to be doing?

PM: Exactly.

SS: Oh, of course, you can do that kind of thing when everybody work for you! You didn’t have to get all the players one at a time from a New York studio or something? You could actually get the band complete and bring in people like ‘NHØP’ [Danish jazz double bassist Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen]. Was he in the [Radio] band?

PM: No. He was partly in the band. Not really. He was travelling so much, that he couldn’t…

SS: Of course, on the original [1983 concert] John Schofield came with Miles. He was part of the ‘package’ if you like?

PM: Right. But John McLaughlin…

SS: Tell us about how John McLaughlin [came in to it] because he wasn’t playing with Miles at the time was he? That was long after…

PM: Yes. Long after.

SS: So how did it turn out that John McLaughlin was on this record?

PM: [Miles] found out that John was playing in a concert hall [in Copenhagen] and he said ‘Get him in! Let him come!’ And John wouldn’t say ‘no’, of course. You wouldn’t say ‘no’ to Miles. So, he came. Completely unprepared. Or, over-prepared, as he always was, because he is fantastic. He had no idea what we were playing and what the themes were. So I asked him, ‘could you please *plays notes on the piano* play these notes?’

He had a rented guitar. A rented amplifier. And he had the piece. We played him some of the score. Some of the things. And Miles said ‘record’ right away because [John] was in the middle of a sound rehearsal [back] in the concert hall that night.

SS: Speaking of that moment, when [Guildhall Jazz Orchestra] perform this, in London, that moment [when the guitar comes in] is going to sound a bit different than it did on the Aura record. Won’t it? We just discussed how, when that guitar first comes in, it comes in gently and then it builds up and then the brass come in… yeah! But the way that John plays it it’s right in your face.

PM: It’s in our face, yes. But not in the piece. Not in the score that you’re playing.

SS: Tell us a little bit about the difference between the original score, the way the piece was played in the first concert for the radio - or nearly the way it was played for the concert, when Miles was there watching and just playing at the end – and the record that you made the next year. What changes did you make when you brought it out on Columbia?

PM: We did it like this, from the beginning. We started from the beginning, we started and Miles commented on it. We recorded it as a song itself. The next one. Exactly the same. Miles commented, ‘I don’t like the guitar there as we have [it]’ and asked the guitarist to do something else or asked the bass player to do this and this. [We] recorded that… you know that… *demonstrates on the piano*…

SS: The reggae…

PM: The reggae kind of thing, yes. [Miles] liked that. Very much. But he did that as a separate tune. Finished. And the next one. And the next one. And then, at the end, we had them so they were mixed like one song at a time. One song. Not like one piece.

SS: And then you re-assembled it into a slightly different order so that it would have impact? So that when you start the CD you’ve got something that’s a little bit like the opening of the piece but for not very long and all of a sudden ‘BANG’, it comes flying in, doesn’t it? With McLaughlin?

PM: So, in a way, the piece that you will be playing is more my idea and the other [studio] one is with the genius hands putting his sparkling light over the whole thing.

On the very night that he got the prize we played that part which I showed you *demonstrates on the piano and sings the drum part* - the Messiaen chord – we played it. The audience clapped. And [Miles] said, ‘play it again!’. [We said to Miles] ‘Are you joining us’. [Miles said] ‘No’. So we played it without Miles and then he came out and he said, ‘Play it again! Now with me’. Because he was supposed to get his prize, you know? So he had to do it again because the guy who was to deliver the check had no idea where we were in the piece! He [had] never heard music like that before. So it was a mishmash, but a lovely mishmash. Miles came in and played three or four times I think.

SS: And nobody’s going to tell Miles ‘no’ are they? He’s like a treasure. You had him for five minutes and all of a sudden you had him for ten and then fifteen… ‘Keep playing!’.

PM: He loved to play over these chords… *demonstrates chords* … that was the trick in the horns.

SS: But Miles didn’t know what the chords were. He didn’t care what the chords were.

PM: No, he didn’t…

SS: He just wanted to be inspired by the sounds.

PM: He said, ‘To me it’s Blues. It’s not Messiaen. It’s Blues.’ He took it like that. He felt these chords were… *plays chords on the piano*

SS: Sort of like a #9 or something? The Blues scale can fit over the top… I find the relationships also, like in the Turangalila Symphony… you know? It’s Blues.

PM: It’s all Blues!

SS: It’s been going on for a long time, hasn’t it? Also, minor third, major third… that’s not exactly the same as the Blues but there’s a relationship there. There’s a dissonance with the #9 and the resulting harmonies… Superimposition, like on the major chord, a third above the tonic in a Blues scale type sound…

PM: Exactly.

SS: That’s also maybe why [Miles] and Gil got so excited about Spanish music, right?

PM: Of course!

SS: So I can see why [Miles] immediately thought, ‘Oh, [Palle]’s on my wavelength.’

PM: I gave [Miles] the Turangalila Symphony as a present. The recording with Bernstein. And November Steps [by Toru Takemitsu] on the other side.

SS: So, in a way, you developed a similar relationship to [that which] Gil Evans had with Miles, didn’t you? I mean, you were learning from each other, you were sharing things from different backgrounds…

PM: I was learning from him… I don’t think they were learning from me!

SS: I don’t mean teaching you but sharing ideas that you had been inspired by and you could [both] relate to, you know? Just like [Miles] with Gil.

PM: I loved when Gil Evans said, ‘Tchaikovsky. The melody maker.’ I loved that. I think of that every time I hear Swan Lake. He respected that [work] so much.

SS: But those guys, like I guess, [you] now know that I know you a little bit, always have open ears for new ideas and, you know, when I heard all those recordings that Alan Lomax made in Spain, when I was working in Spain… I was listening to Alan Lomax’s recordings of Galician music and right there, all of a sudden, there were all the tunes that are in Sketches of Spain. Gil and Miles must have been listening to this music!

PM: Of course they did!

SS: ‘Wow, how does that music work? That’s like our music!’

PM: I am very, very pleased that you, Scott, and [Guildhall Jazz Orchestra are performing AURA] and I’m sure it will be it will be appreciated up there *points to the sky* where [Miles] is. Like he said about Gil Evans, ‘Gil Evans is not dead… he’s not dead… he’s just changed.’ He said that. He didn’t want [Gil] to be dead. Gil Evans was supposed to write a piece for the same [Leonie Sonning’s] Prize celebration concert, but Miles said, nicely, on the elevator, ‘Gil was supposed to be here’. ‘I know’, I said. [Miles said] ‘He’s sitting home listening to overtones’. Isn’t that beautiful?!

SS: That’s fantastic! That gives you a kind of insight into the relationship, into the way they talked to each other!

PM: Yes! It’s just like two small boys are two grown-up masters. Yes.

SS: Oh, that’s amazing.

PM: So, that whole area of my time with Gil Evans, which I loved – I think that man was a Buddhist monk. He said, ‘I just orchestrated it like Duke Ellington [but] with other instruments’.

SS: I think he slightly underestimated himself there!

PM: I think so!

SS: But, I know what you mean. It’s true. You can trace the ideas, of course. There is something very true in that.

PM: [Gil] was so underrating himself. He was a master. Never to forget Gil Evans. He inspired us all. Also those who don’t know it!

SS: One last thing, it’s a little bit different, but, we’ve talked a lot about Miles Davis and about [Aura], but what about all the other things which you’ve done, because this is only one small part of your life really, I mean, you’ve worked with musicians from all over the world and you live in Copenhagen and not only have you played, obviously, a lot ‘at home’ but you’ve worked with a lot of other people coming through here, or going out of here. Maybe, like London, Copenhagen was a place where many people came to?

PM: It was.

SS: … and you became the person of connection for many of them. Is that true?

PM: I don’t know. My role is very timid, I think. But, for me, it was a great time with the Americans, like George Russell and Dexter Gordon, who I worked with and wrote the Strings [and Things] for ‘Dex’. And Bill Evans I met and wrote for as well. And I remember how timid I was in those days. When Gil Evans came over to play at the old [Jazzhus] Montmartre [in Copenhagen], Johnny Coles forgot his passport and couldn’t leave America before the next day. So Herluf [Kamp-Larsen], the owner of the club, called me and said, ‘Come in and play with Gil Evans Orchestra’, because Johnny Coles couldn’t make it. I said, ‘No, I don’t dare!’ I didn’t want that. Then [Herluf] called again and said, ‘Come on! That’s sh*t I don’t wanna hear from you! Come on! Be a man. Take your trumpet. Come in here. They need a trumpet player.’ So, I came in and that was my first night with Gil Evans. Years and years and years ago. And you can see here… *turns to the shelves behind* the little picture I have of me and Gil from that period.

SS: That’s fantastic. It’s a great picture of both of you.

PM: He was fantastic. What a person. How can you be so soft and still survive in that world? I said to myself, ‘How can you?’ Of course, I didn’t say anything about that [to Gil]. And then we did the tour with Miles [Evans] and Noah [Evans], [Gil’s] sons.

SS: But then you also had [musicians], not only coming from America, but coming from other countries in Scandinavia and also you mentioned about [musicians] from South Africa – Dollar Brand [Abdullah Ibrahim] – and musicians must [have] been coming from Eastern Europe, you know?

PM: I had not so much to do with the Eastern Europeans, although they were here, and [made] a fantastic mark on [Denmark’s] musical culture – like [Krzysztof] Komeda, if you remember Komeda? I wasn’t much involved in [those] circles. I was there when they recorded, but I was just sitting there, doing nothing. And ECM, I worked with ECM a lot. With Terje Rypdal’s groups. Beautiful guitar player from Norway, as you, probably, may know. And Jon Christensen. We had a trio for many years and did a couple of recordings for ECM. And so on and so on.

SS: We haven’t even said, in this interview, about your trumpet playing. I mean, if someone watching [or reading] this interview didn’t know you they might say, ‘Is he just a composer? Or, is he a piano player like Gil Evans?’, but you’re not!

PM: I’m not! I’m none of that. I’m basically an almost fulfilled trumpet player.

SS: That’s nice to hear! That’s pretty good!

PM: I still have my trumpet. My old Martin [trumpet make], yes. I had Martin before I knew that Miles had Martin. I had this one before Dizzy [Gillespie], you know?!

SS: No kidding!

PM: Dizzy had this mouthpiece as well. The Al Cass.

SS: … and your flugelhorn too, I see.

PM: The flugel as well, yes. And that’s why I felt ‘home’. I felt that my message was there. If I could make that happen, I would end happy. But then, Miles came in the way! And you came in the way! And all you *gestures to the camera* people came in the way wanting to do a 40 years tribute, a fantastic 40 years tribute to the piece.

SS: You know, I wasn’t interested in doing [Aura] because it was a [40 year] tribute. I was interested in doing it because I really like the music.

PM: I’m very pleased.

SS: You know, sometimes you do projects, and we’ve talked about a few of them, and I’ve done quite a few historical, you know, repertory projects. You try to recreate as much as you can of the sound of Duke Ellington or any of those orchestras or anything in the past and, like doing classical music, like doing Bach, the music is still alive, of course, and it has its own [resonance], but sometimes it feels ‘of a period’ and even though the recording you made with Miles using things like we don’t use very much anymore, like the Simmons drums and some of the synthesizer effects, but I listen to them now and they sound fresh to me again. They sound right. In the same way that a period instrument sounds right when you do Bach or even the horns for a Wagner or something, they fit the language of the music so well. So, I wanted to do this piece because I really wanted to experience standing there – I have to say, I do this totally selfishly, all these pieces, nobody realises, I mean, I wanted to do [Charles Mingus’] Epitaph because I wanted to be right in the middle when all that sound comes at me. Not because of ‘I want to be in charge’ but because I want to have the best seat in the house. And that’s what you get as a conductor for these sorts of pieces with wonderful sounds.

PM: Exactly.

SS: So that’s the reason I think we want to play it. Because we want to experience the music.

PM: What a lovely attitude to the piece!

SS: … and if we get the benefit of somehow learning about the past and learning about you and some insight into Miles, that’s a bonus. But, really, the idea is just to experience wonderful music, you know? That’s what I think it is.

PM: Thank you. What a pleasure. And thank you and good luck!

Biographies

Matt Skelton

Acting Head of the Guildhall School Jazz Department, Matt Skelton is a drummer equally at home in modern and vintage Jazz styles enjoying a diverse musical career that has already spanned three decades. He has accompanied many leading Jazz luminaries such as Harry ''Sweets'' Edison, Conte Candoli, Bucky Pizzarelli, John Pizzarelli, Warren Vache, Scott Hamilton, John Hendricks, Kurt Elling, Curtis Stigers, Gregory Porter, and most recently Georgie Fame; and recorded and appeared with singers such as Marion Montgomery, Dame Cleo Laine, Claire Martin and Dame Jessye Norman.

Tony Kofi

Tony Kofi is a British Jazz multi-instrumentalist born of Ghanaian parents, a player of the Alto, Baritone, Soprano, Tenor saxophones and flute. Having 'cut his teeth' in the "Jazz Warriors" of the early 90's, award-winning saxophonist Tony Kofi has gone on to establish himself as a musician, teacher and composer of some authority. As well as performing and recording with Gary Crosby's "Nu-Troop" and "Jazz Jamaica", Tony's playing has also been a feature of many bands and artists he has worked/recorded with include "US-3" The World Saxophone Quartet, Courtney Pine, Donald Byrd, Eddie Henderson, The David Murray Big Band, Sam Rivers Rivbe Big band, Andrew Hill Big Band, Abdullah Ibrahim, Macy Gray, Julian Joseph Big band, Harry Connick JR, Byron Wallen's Indigo, Jamaaladeen Tacuma's Coltrane Configurations and Ornette Coleman.

Miguel Gorodi

Miguel Gorodi is a London based composer, teacher and trumpet player performing across a broad spectrum of jazz and improvised music. He currently leads and writes for the Miguel Gorodi Nonet, and co-leads the Gorodi/Ingamells duet ensemble and the Gorodi/Braysher Quartet. He is a member of the Barry Green Sextet, SEED Ensemble, the London City Big Band and the Dixie Ticklers, as well as regularly playing for the London Jazz Orchestra.

Scott Stroman

Scott Stroman is the director of the London Jazz Orchestra, Eclectic Voices, artistic director of Highbury Opera Theatre, and a composer, conductor, and performer in both jazz and classical music. He directed the London Philharmonic Orchestra' s Renga and Hit Squad ensembles and directs conducts orchestras, choirs, opera and jazz throughout the UK and Europe. He founded the Guildhall Jazz Orchestra and with them premiered all the Miles Davis / Gil Evans collaborations in the UK, Mingus' Epitaph, Ellington's Black, Brown and Beige, Rufus Reid's Elizabeth Catlett Suite, his own reimagined suites from Coltrane's Africa/Brass, Ellington's Second Sacred Concert, and the Jazz Messengers' Moanin in addition to countless pieces by British and student composers.

Robbie Robson

Robbie leads his own band 'Dog Soup' and regularly works with the Matt Wates Septet, Frank Griffiths Nonet and the London Jazz Orchestra. He has played and worked with John and Jacqui Dankworth, Jamie Cullum and JTQ, amongst others. He was a national finalist in the Young Jazz Musician of the Year 1999, and the runner up in the Perrier Young Jazz Musician 2000.

Oliver Nelson

Oliver Nelson was a distinctive soloist on alto, tenor, and even soprano, but his writing eventually overshadowed his playing skills. He became a professional early on in 1947, playing with the Jeter-Pillars Orchestra and with St. Louis big bands headed by George Hudson and Nat Towles. In 1951, he arranged and played second alto for Louis Jordan's big band, and followed with a period in the Navy and four years at a university. After moving to New York, Nelson worked briefly with Erskine Hawkins, Wild Bill Davis, and Louie Bellson (the latter on the West Coast). In addition to playing with Quincy Jones' orchestra (1960-1961), between 1959-1961 Nelson recorded six small-group albums and a big band date; those gave him a lot of recognition and respect in the jazz world. Blues and the Abstract Truth (from 1961) is considered a classic and helped to popularize a song that Nelson had included on a slightly earlier Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis session, "Stolen Moments." He also fearlessly matched wits effectively with the explosive Eric Dolphy on a pair of quintet sessions. But good as his playing was, Nelson was in greater demand as an arranger, writing for big band dates of Jimmy Smith, Wes Montgomery, and Billy Taylor, among others. By 1967, when he moved to Los Angeles, Nelson was working hard in the studios, writing for television and movies. He occasionally appeared with a big band, wrote a few ambitious works, and recorded jazz on an infrequent basis, but Oliver Nelson was largely lost to jazz a few years before his unexpected death at age 43 from a heart attack.

Palle Mikkelborg

Palle Mikkelborg is one of Denmark’s most influental and original jazz musicians. As a child, he received lessons in playing trumpet, but apart from that he is self-taught. He has been inspired by jazz musicians such as Miles Davis, George Russell and Gil Evans but also by composers such as Ravel, Messiaen and Charles Ives.

Since the 1960s he has challenged the musical conventions with his personal trumpet playing, ambitious orchestrations and compositional crossover projects. Mikkelborg has his own both lyrical and dramatic style. A lot of his music has a very spacious character, which is also reflected in his use of unusual orchestrations and electronics. Furthermore, his compositions have a spiritual quality to them, as can be heard in Going to pieces without falling apart (2002) or My God and my All (1991).

Guildhall School of Music & Drama

Founded in 1880 by the City of London Corporation

Chairman of the Board of Governors

Graham Packham

Principal

Professor Jonathan Vaughan

Vice-Principal & Director of Music

Armin Zanner

Vice-Principal & Director of Production Arts

Andy Lavender

Head of Opera Studies

Dominic Wheeler

Please visit our website at gsmd.ac.uk

Join the Events Mailing List

Sign up to our events mailing list to hear about upcoming events and broadcasts from across Guildhall School.

We hope you have enjoyed today’s performance at Guildhall School. If you are interested in supporting world-class training for these talented performers and production artists, we would be grateful for a voluntary donation. You can make your gift using our GoodBox devices located at the Box Office and foyer bars, or text* GSDONATE to 70970 to donate £5. Please speak to the front of house team if you require assistance.

Fundraising, payments and donations will be processed and administered by the National Funding Scheme (Charity No: 1149800), operating as DONATE. Texts will be charged at your standard network rate. For Terms & Conditions, see www.easydonate.org